What do you see when you look out into the world? Do you notice auric gold ribbons of sunlight dappling through the leaves of a tree and feel the warmth of a happy memory? Are your eyes satiated by the plump scarlet flesh of a summer sweetened tomato? Do you move when you see the icy optic viridian of a traffic light signalling you to go?… Everyday life is full of fleeting glances of colour, and though the smallest may seem transient or abstract, these visual signs can grant a wealth of information.

A question of colour

Colour has always left a tint in my life; from studying at art school and creating artworks, to communicating my research, recalling my strongest memories, and shaping the way I interact with the world. Even now as I walk the steps into Librarianship, I aid creative arts students with their contextual research, and must think seriously and practically about colour. I have encountered queries that have ranged from ‘Do you have any information on the colour red and how painters have used it?’ to ‘Do you have information on fashion designers who have subverted the use of white in bridal couture?’. Colour is a powerful visual language and a primary tool for artists to create and communicate information. So what is colour as information? Is it truthful and evidential, or is it subjective and ambiguous? By looking introspectively at the facets of colour, perhaps it can tell a better story of information itself, what it is, and how it can be communicated.

Splitting open the sunbeam

Before I start wandering dreamily over the shades of blue, let us first apply some exacting science. Colour is the subjective physiologic interpretation of the visible electromagnetic spectrum. As a ray of light enters your eyes, bright ambiences or images, produced in the retina, are sent to the brain and interpreted as a set of chromatic sensations. The reason different things appear different colours, are because like tides passing through the ocean, light travels in waves too. (Evans, 2017). While some things absorb some wavelengths of the visible spectrum, others are sent bounding off into the heavens. Blue light for example, is scattered in all directions by tiny molecules in the air of the Earth’s atmosphere. This light travels in short, small waves, and when it touches your eyes and your brain processes the data, the sky appears to breathe out an all-encompassing colour blue. The absence of these light waves at night is also what turns the sky into a black cauldron, enabling us to see the glitter of distant stars. In this sense, the colour we really perceive something to be is precisely the colour it isn’t, that is, just the segment of the spectrum that is being reflected away. (St Clair, 2016).

Colour as information

Colour is a very sophisticated neural process and the specific biochemical reaction results in the organisation of what is conveyed or represented by the arrangement or sequence of light. (Nichols, 2014). It is evidential so surely it must be information? Information is notoriously mercurial, it exists in abundance, and like running water it takes shape and significance depending on the environment and need. The father of information theory Claude Shannon (1993) was hesitant with definition, stating

“it is hardly expected that a single concept of information would satisfactorily account for the numerous possible applications of this general field”.

The different interpretations, misunderstandings, and misuses of information are more evident now we are living in such a hyperconnected and information sharing society. This is what Floridi (2014) describes as the 4th revolution, where contemporary life has become immersed within a swirling cloud of data. The news, social and digital media, technology, and analytics, all filter swathes of data and downpour us with varying types of information. Whether we like it or not, there is not a part of our lives now were we don’t get soaked in the stuff.

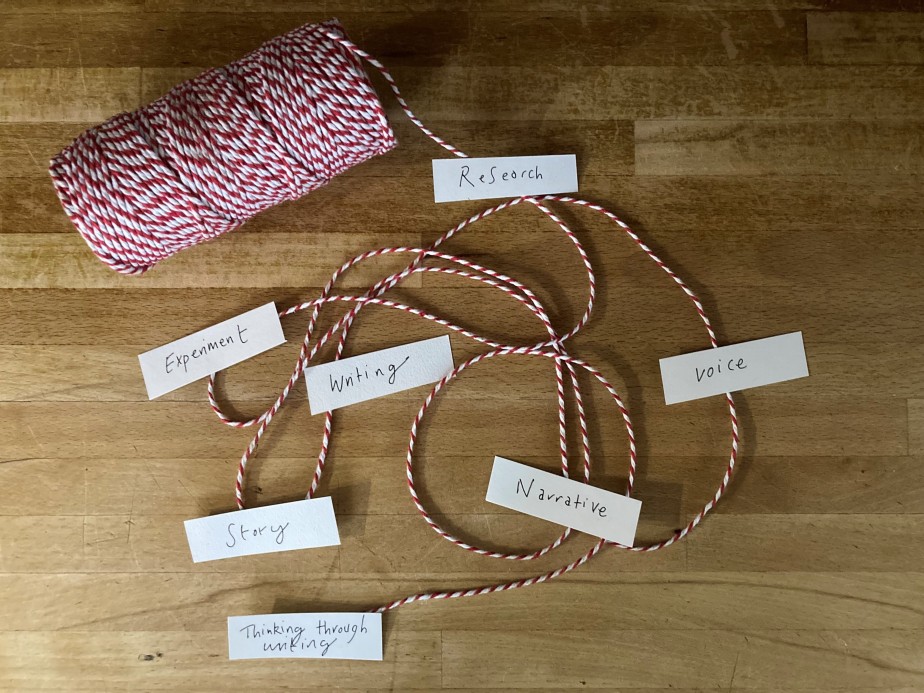

Floridi’s (2010) General Definition of Information (GDI) is a single map of informational concepts and this nifty model is now commonplace in fields that reify information, to be organised and disseminated, such as the library and information sciences. By applying this model across domains, we can start to decode complex information and think of it as a structure of data + meaning. Using this model, we can also start to understand non-textual forms of information, beyond the frame of the written word. Although not always obvious, images, objects, and even performances containing the same pattern of data + meaning, can be credible sources of information.

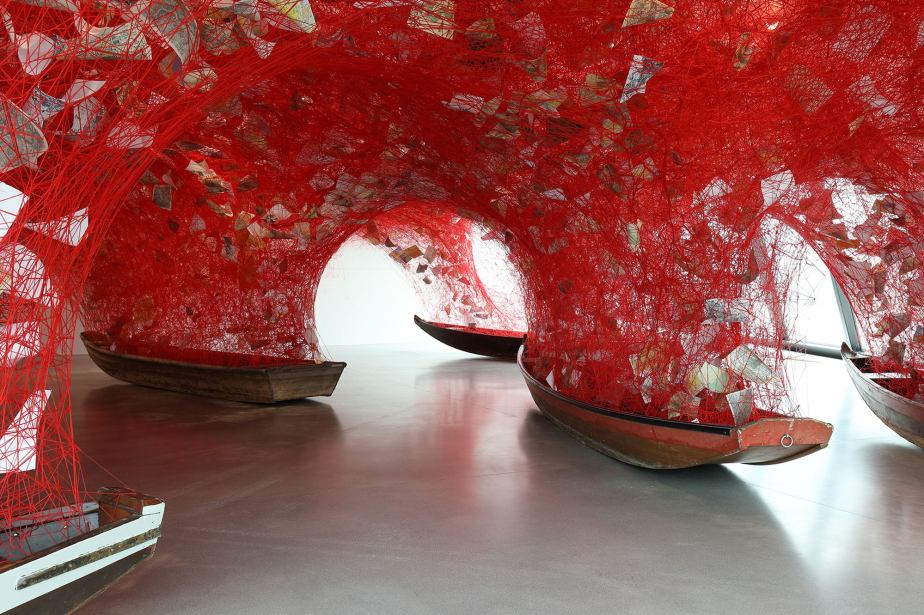

Our understanding of the many practical uses of colour to communicate, has in turn enabled us to interpret and transcribe everything, from mundane objects to the illimitable architecture of the cosmos. Even though it seems impossible to imagine a world where the colour of something could not be used to visualise, describe, inform or understand, the textual use of colour has historically entered the written language very slowly. The ancient Greeks, with all their beautiful and poetic prose, never had a simple word for the colour blue. The seas and skies of their world were described as ‘wine-dark’, ‘starry’ or ‘of lead and bronze’. (Michela-Sassi, 2017). Similarly, in the middle ages there existed no word for the colour orange, and today there are desert tribes in Africa who have six words for the colour red, and yet no single one for green. (Fletcher, 2001). Through the eyes of observation and understanding, it has become clear that every culture has its own way of understanding, organising, classifying, and communicating with colour. This is not due to varying biology of the human eye, but because colour is subtle and prompts varying emotional responses, all according to varying social, political and cultural contexts. The complexity of colours conveys numerous types of information from feeling, relationships and contrasts, dramas and tensions, to the very nature of matter and its processes and transmutations. Once understood and harnessed, colour can be used to suggest temperament, class, vocation and hierarchy, and as such can define, differentiate and blend well formed data. (ARAS, 2010). There are entire industries that use and are highly dependent on libraries of colour to communicate information; it can be applied to weave a piece of clothing as equally as a work of art, design or product, and logo or brand.

Shades, hues, and tints of information

Colour as information triggers different responses. It can be environmental, a cold fact, usefully and efficiently giving meaning to data. A red light is a signal or warning, a well-placed green on a topographic map distinguishes land from water, and a green banana turned yellow is ripe to eat. (Tufte, 1990). What is more interesting, particularly for the business of artists, is that colour can be a tool of subtle visual communication. It can draw from cultural knowledge and create a story, trigger or carry deeply truthful or emotive information, invoke a memory, stimulate the senses, and rouse the soul. It can also be unnatural, juxtaposed, playful, and subverted to change to the status quo. (Paul, 2017). It can be both truthful and universal as well as highly subjective and interpretive. Understanding information, and the many forms it possesses, is especially important for library and information professionals. It is after all our responsibility to collect, protect, preserve, manage and disseminate meaningful information to society. To understand information, context and critical thinking are therefore paramount. It is our ability to critically evaluate its contents, that allows us to judge its meaning, purpose, and be able to act on it. As with any language, the language of colour and information is learned. By widening the understanding and teaching of visual and information literacies, Librarians can bring clarity to a deluge of information and assist researchers with applying more creative and practical ways of giving meaning to data.

So perhaps then when you walk to work in the morning, you may take the time to notice some colour in your day and think more about what it is telling you. Let the amber corona on the edges of leaves whisper to you that autumn’s hand is near. Read the gaudy yellow billboard at the bus stop you always walk past. Stand in front of an abstract painting, or the bright cerulean sky and let the colour wash over you. Life is showered with waves of light, colours, sensations, and complexity, and you will begin to see that even in the mundane there is information to be read and little bit of magic.

References:

Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism (2010) The book of symbols: reflections on archetypal images. London, UK: Taschen. p636.

Evans, G. (2017) The story of colour: an exploration of the hidden messages of the spectrum. London, UK: Michael O’Mara Books Limited. p14-15.

Fletcher, A. (2001) The art of looking sideways. London, UK: Phaidon Press. p53.

Floridi, L. (2010) Information: a very short introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p19-24.

Floridi, L. (2014) The 4th revolution: how the infosphere is reshaping human reality. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p13-17.

Michela-Sass, M. (2017) ‘The sea was never blue’. Aeon. Available at: https://aeon.co/essays/can-we-hope-to-understand-how-the-greeks-saw-their-world (Accessed: 30th August 2018).

Nichols, W. (2014) ‘The Sense, the Body and the Big Blue’, in Blue Mind. London, UK: Little, Brown & Company. p88-89.

Paul, S. (2017) Chromophilia: the story of colour in art. London, UK: Phaidon Press. p11.

Shannon, C. (1993) Collected papers. New York, USA: IEEE Press.

St Claire, K. (2016) The secret lives of colour. London, UK: John Murray Publishers. p13-15.

Tufte, E. (1990) Envisioning information. Connecticut, USA: Graphic Press.

Illustrations:

Bell, A. (2018) Splitting a sunbeam [photograph] UK.

Floridi, L. (2010) Information: a very short introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p30, diagram.